Circumnavigation 2020 onwards

Sharing our adventure with friends

● Latest Post

● Previous Posts

-

The Maldives

Oceanic Whitetips are on the critically endangered list and in Nov 2025, they were added to CITES Appendix 1, the highest protection prohibiting any trade.…

-

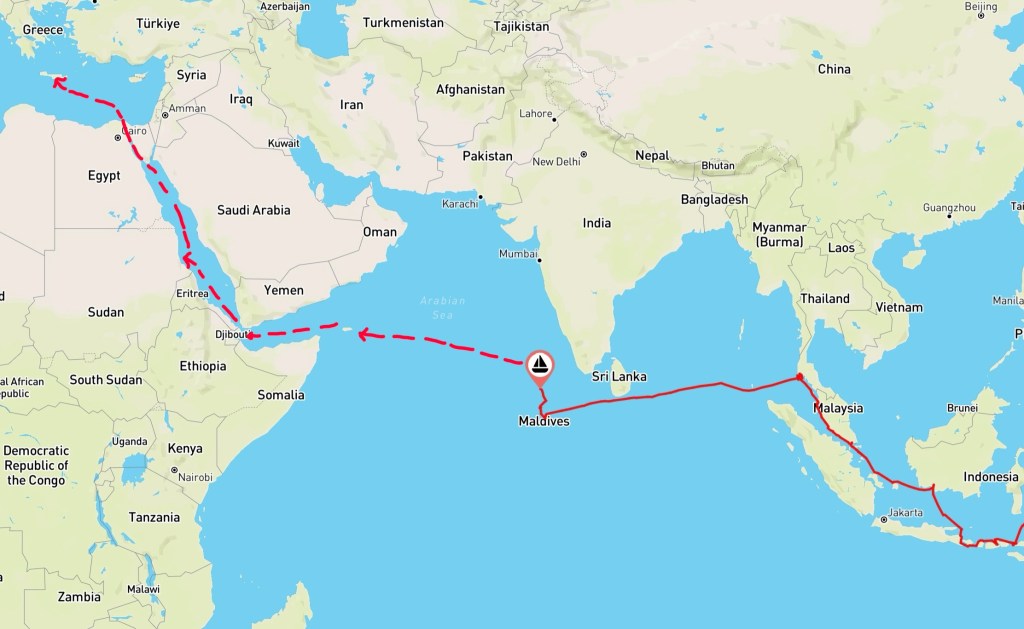

The big crossing

Ann’s dad passed away this month—and the origins of a crazy adventure like this can be traced back to the values a parent instills in…

-

Komodo National Park

The Komodo dragon’s hunting strategy is to ambush its prey & with one venomous bite that significantly tears the flesh, the venom prevents blood coagulation…

-

Banda Neira, Indonesia

Banda Neira, a tiny island in the Banda Sea, was the only source of nutmeg in the world. The Bandanese people voyaged to Java and…

● About Us

Yo! It’s Ann and Ian on our 1984 Wauquiez Amphitrite. Photos & blog by Ann, keeping us afloat and moving forward by Ian.

● Of interest

The UN High Seas Treaty came into force Jan 17 2026 – we can have 30% of Oceans a marine park and have a well-regulated global fisheries

Great podcast from Outside Magazine about military parajumper training in breath holding

See this story of Cook Islanders shipwrecked on Minerva Reef in 60s (film coming soon)

BBC Planet Earth: pack hunting – first documentation of snakes hunting the marine iguana in Galapagos

Book Rec’d: Christina Thompson The Sea People on ancient Polynesian Navigation (this is sooo good)